In the investment parlance, Diversification is the process of spreading out risk by investing in a portfolio of several stocks; such that even if one fails, the others will be able to support the portfolio. While there is merit in the theory of diversification, mindless addition of stocks is likely to diversify return rather than risk.

A diversified portfolio’s return will always be lower than the return of the best performing stock, but more importantly, it will also be higher than the worst performing stock leaving the returns somewhere near the Mean. Scholars have tried hard to create methods in order to optimise this Mean Return. The most popular among them is the Capital Asset Pricing Model (or popularly CAPM), which is a derivate of Harry Markowitz’s Modern Portfolio Theory. This method is predominantly used today by most investors and fund managers to evaluate the effect of diversification/risk in a portfolio. Without getting too much into the technicality (…and short comings of the theory), CAPM talks about two risks, Systematic and Unsystematic risk. Systematic or non-diversifiable risk is that which is present in the system (market risk-b). These are risks which cannot be eliminated. Unsystematic or diversifiable risk are those specific to a particular stock. It is to reduce this unsystematic risk that investors/fund managers add more stocks and diversify their portfolios.

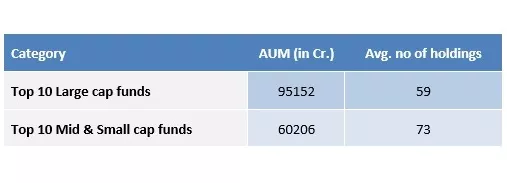

A quick review of the portfolio of most Mutual Funds reveal a long list of stocks, some even longer than the index itself. Which brings us to the basic question, why pay a fund manager to invest in such a broad portfolio which entails so much cost and brings down your returns. One might rather recreate the same returns by just buying into the Index ETF. If a fund manager holds a large number of stocks in the portfolio, he/she is either confused, extremely cautious or there is lack of liquidity in the stocks selected. Either way the portfolio is at RISK of under performance!

Enter the

‘Sage of Omaha’ –

“Wide diversification is only required when investors do not understand what they are doing.”

The diversifiable /stock specific risk can be overcome even with a concentrated portfolio of companies. The stocks selected should have unrelated business models, different demand drivers and sufficient liquidity. These stocks would move in an uncorrelated fashion and offer a perfect hedge against each other. It will also help achieve above average return at a much lower cost. Further the schematic allocation of cash will effectively preserve capital when times are wary.

Investors also assign arbitrary caps to single stock exposures in their portfolio (5%,10% etc.). This is done in an attempt to control the risk induced by a single company. Since there is only limited allocation of capital in this case, the rest will have to be allocated to other companies. In most cases the investor tends to select mediocre stocks just to fill the bucket. This is a meaningless exercise and counter-productive. Instead, the investor should pursue further research and arrive at the decision on whether to increase/decrease the exposure based only on the company’s potential. It is always better to invest 50% in a good company rather than 5% in 10 bad ones.

Judicious use of capital and clear understanding of risk are essential while constructing a portfolio. Risk cannot be reduced by confining it within arbitrary numbers. It is more of a philosophy. While Diversification is a useful tool in Risk management, it will have to be used properly for effective results. Meaningful diversification shouldn’t be about adding several companies to the portfolio, rather it should identify the essential and eliminate the rest.